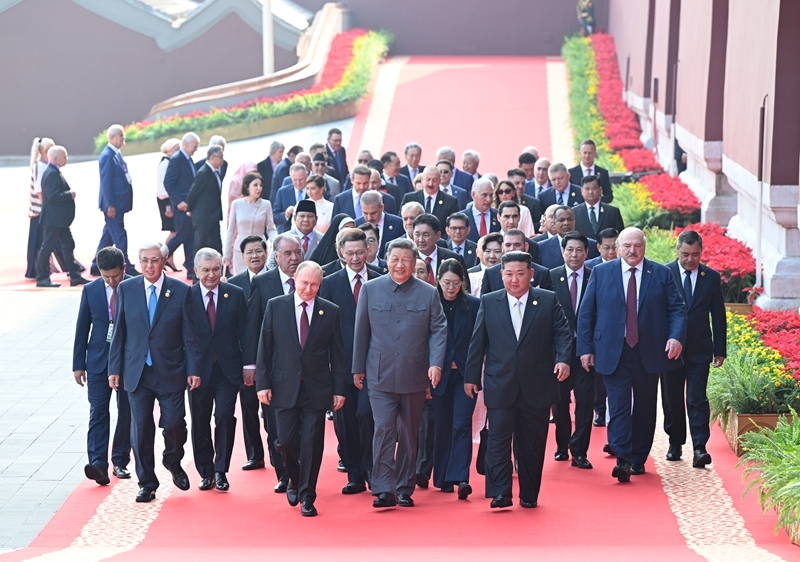

Another major signal the parade has sent to the international community, and especially to the West, that Beijing is more willing and able to make use of its own expanding network of friends and supporters, through bilateral diplomacy but also via organizations like the SCO and the recently expanded BRICS-plus grouping, to cement China as a strategic hub and an opposing pole. Picture source: PRC, September 3, 2025, gov.cn, https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202509/content_7038994.htm.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 53

No Rain on This Parade: New Directions for China’s Military Thinking?

By Marc Lanteigne

In the wake of what would become the grandest and arguably the most internationally scrutinized summit in Tianjin of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in late August, many eyes were already on China as the Xi Jinping regime oversaw an expansive Victory Day parade in Beijing on September 3 to observe the 80th anniversary of the end of the Pacific War in World War II. For all intents, the parade ultimately served two major functions for Beijing: namely to demonstrate China’s evolving military prowess, and to place a spotlight on the country’s expanded strategic goals. The latter included a gathering of not only leaders from fellow SCO members, including Russia’s Vladimir Putin, President Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus and Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, but also other regional friends at odds with the West, with North Korean General Secretary Kim Jong Un receiving by far the most attention within that cohort. Sino-North Korean relations had been seen as cooling after Pyongyang began to align closer to Russia in recent months and with the DPRK agreeing to send several thousand forces to assist the Russian military in Ukraine. However, Xi and Kim ultimately used the parade to re-confirm their friendship and fortify the two states’ security cooperation.

The PLA Under Strain

Both the SCO Summit and the parade acted as a coming-out party of sorts for China after the country experienced several shocks in the form of post-pandemic economic slowdowns, mounting economic pressure from the West, and questions about the relationship between party and the military amid a continuing crackdown on corruption within civilian and military circles. Despite a longstanding tradition observed by Xi’s predecessors that high-ranking officers in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) were not to be subject to political dismissals, Xi himself has not demurred from removing two ministers of defence, Generals Wei Fenghe and Li Shangfu, in rapid succession in 2023, with PLA Navy Admiral Miao Hua, then-Director of Central Military Commission’s Political Work Department, also being ousted in late 2024 for alleged disciplinary violations. As well, a vice-chair of the CMC, General He Weidong, disappeared from public view earlier this year amid reports that he was being investigated for corruption.

These removals have demonstrated Xi’s resolve in ensuring party loyalty among the armed forces, filtering out corruption within the PLA, while ensuring that the military is prepared to address new frontiers of warfare. With the dissolution of the PLA’s Strategic Support Force (PLASSF) in April last year, the successor “four arm” system (Aerospace Force, Cyberspace Force, Information Support Force, Joint Logistics Support Force) underscores the greater visibility of cyber- and information warfare to Beijing’s long-term strategic planning. Thus, another effect of the parade was to display China’s military modernization but also sent the unambiguous political message that despite incidents of internal discord, Xi was still very much in command of the military.

The Parade and Strategic ‘Swaggering’

Nonetheless, the Victory Day Parade was also the perfect venue for Beijing to unveil its newest advanced air, land, and sea weaponry to both domestic and global audiences. The parade first and foremost demonstrated the innovation and diversity of current Chinese weapons capabilities. This was in keeping with the cold war-era practice of “swaggering,” often described as deploying military power not for direct defence or offense but for the purposes of raising national pride, augmenting regime security, and demonstrating force proficiencies to outside actors. Moreover, these displays underscored China’s proficiency in indigenous weapons development, after a long period of being dependent on Russian assistance and models. As Sino-American relations are now tenuous at best, many of the weapons displayed at the event could be viewed as countering U.S. strategic interests in the Asia-Pacific. Among the offensive weaponry introduced was the intercontinental, very long-range Dongfeng-61 missile which may be able to house multiple nuclear warheads, as well as the Julang-3 intercontinental submarine-launched ballistic missile. The Dongfeng-26, a previously known intermediate range missile, often nicknamed the “Guam-killer” as it was seen to be useful against American positions there, was also on display with variants of anti-ship missiles including the supersonic Yingji-21. The message sent by these weapons to the United States and its allies was not ambiguous.

A greater emphasis on drone warfare was also illustrated during the parade, including China’s ability to repel drone attacks via new laser weapons on display. The “LY-1” laser system was advertised as being effective against enemy drones and missiles, and could be used on land or sea. Beijing has also been working to better incorporate artificial intelligence into its drone systems for faster responses. Two Chinese-made drones debuting in the parade which signified considerable technological jumps were the Gongju-11 aerial drone, for its purported ability to accompany traditional fighter jets during attacks, and the AJX-002 “giant” submarine drone. Chinese military researchers have been enthusiastic about making use of drone swarms, in conjunction with other defensive weaponry, to deter attacks near Chinese soil.

Strength in Numbers?

Another major signal the parade has sent to the international community, and especially to the West, that Beijing is more willing and able to make use of its own expanding network of friends and supporters, through bilateral diplomacy but also via organizations like the SCO and the recently expanded BRICS-plus grouping, to cement China as a strategic hub and an opposing pole. One lingering question however is whether these displays of unity are a harbinger of new Beijing-led strategic constellations, or more of a showpiece demonstration of unity against the West. Certainly, there are still questions about the depth of Chinese strategic partnerships with other key players, including Russia.

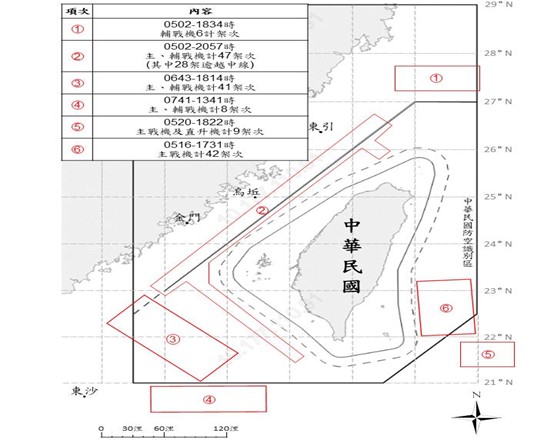

On the eve of the parade, the Chinese government announced a new “Global Governance Initiative” (GGI) which included calls for “greater democracy” in international relations, respect for sovereignty, support for multilateralism, and the adherence to international law without “double standards.” Despite these calls, however, the immediate effects of both the SCO Summit and the Victory Day parade may be a still-more assertive Chinese strategy, fanning concerns throughout the region about potential expansionism in the Western Pacific. These concerns have prompted many East Asian governments, including Taiwan’s, to increase defense spending and pay closer attention to both traditional and “grey zone” military threats. This at a time when stresses have appeared between many of the United States’ partners in both Asia and Europe, along with questions as to the direction of Washington’s Pacific policies, and a rethinking in many regional capitals about emerging security policy priorities.

(Marc Lanteigne is a professor of political science at the Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, and an adjunct lecturer at the University of Greenland, Nuuk.)