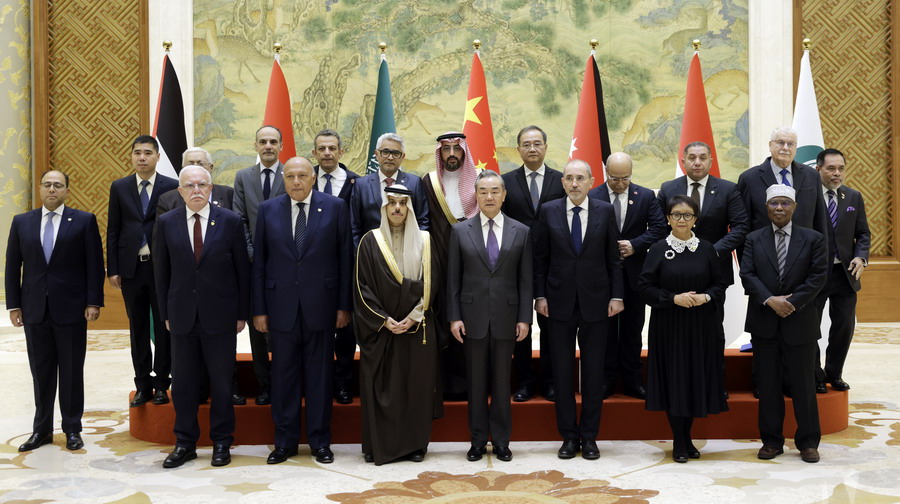

Once again, Syria is redrawing the geopolitical map, that will reflect the evolving global order. On one hand, the influence of major powers such as the U.S., Russia, Europe appears to be shrinking. On the other hand, regional players such as Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar are becoming more assertive. Picture source: Syrian Finance Department, December 10, 2024, https://syrianfinance.gov.sy/pages/photos/a173391010752a470056318_898484885803066_7561128174770192623_n.jpg

Prospects & Perspectives No. 11

Syria as a Geopolitical Turning Point

By Petr Tůma

At the time of the civil war, Syria became a major geopolitical turning point. The Obama administration’s decision in August 2013 not to enforce his own “red lines” regarding the Bashar al-Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons clearly confirmed the ongoing U.S. retreat from its superpower status. At the same time, it marked Russia’s return to the global stage when Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov negotiated a diplomatic off-ramp for Assad. In 2015, Moscow once again saved Assad when insurgents threatened the regime’s survival. Western dignitaries and experts predicted that Russia’s intervention in the Syrian maelstrom would turn into its second Afghanistan.

In only a few days leading up to Assad’s fall on December 8, Syria once again became the focal point of regional and global politics. The regime’s collapse upended Iranian and Russian control over Syria and significantly weakened their regional stances. Tehran lost its closest allied capital, its land bridge to the Mediterranean, access to border with Israel, and the connection to the West Bank. Russia is likely to lose Tarous port, its only naval base in the Mediterranean, as well as the Hmeimim military airport, crucial for airlifting supplies to its military ventures in Africa, including operations of Africa Corps (former Wagner Group).

Once again, Syria is redrawing the geopolitical map, that will reflect the evolving global order. On one hand, the influence of major powers such as the U.S., Russia, Europe appears to be shrinking. On the other hand, regional players such as Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar are becoming more assertive.

The key U.S. role: Yet shrinking

The U.S. remains the key reference point for the new rulers in Damascus. Ahmad Sharaa, president for the transitional period, cannot succeed without Washington’s backing, even if U.S role were to be limited in the future mainly to the political. For now, the U.S. still has about 2,000 military personnel deployed in northeast Syria in the framework of the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS. This presence has also helped protect Syria’s main oil and gas fields from regime capture and — importantly — has also deterred Turkey from further interventions against the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which played a crucial role in countering ISIS but is accused by Ankara of links to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

The latest developments on the Syrian chessboard have reinforced the latter reason for the U.S. presence. Ankara is trying to use the window of opportunity and was threatening the push against Syrian Kurds. Damascus is trying to offer the solution and is pressuring the SDF to disband and integrate into the Syrian army. The interim government has set this as a condition for participating in the national dialogue that will outline a new constitution. While most rebel groups, including Ahamd Sharaa’s own Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), have agreed, the SDF remains reluctant, and for some reasons.

Washington should not withdraw before securing an agreement between the SDF and Damascus that guarantees Kurdish rights and ensures their representation in the new government. The threat of ISIS also remains and any destabilization stemming from Turkish intervention or reckless U.S. withdrawal could help ISIS to regroup, particularly in areas that once served as its stronghold. Moreover, the SDF currently manages prisons holding over 9,000 ISIS fighters and tens of thousands of their family members. For the SDF integration into central government’s forces, Damascus still needs to convince international partners that it can effectively replace the SDF in the fight against ISIS.

As President Trump repeatedly spoke about pulling U.S. troops from Syria — and nobody knows whether or when he will do so — the Pentagon has allegedly drafted plans for a full withdrawal within 30, 60, or 90 days. A black swan event could arise from Trump’s interactions with Turkish President Erdogan, as happened in 2019 when Trump unexpectedly ordered a U.S. military departure. This decision led to the resignation of then-Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and was later partially reversed after pressure from officials like Jim Jeffrey, then Special Envoy for Syria and D-ISIS. However, the damage had already been done with the Russians and the regime settled in the former U.S. bases.

If Trump would now push for withdrawal, one possible compromise could be pulling troops from the al-Tanf base near the tri-border area with Jordan and Iraq — an area critical for countering ISIS and Iranian proxies. This would present fewer risks than evacuation from the Northeast.

Other major powers: Limited engagement

Regarding other major powers, it is unlikely that the EU will play a decisive role in Syria, despite initiatives such as February Paris Conference or the Brussels IX. Pledging conference to be held in March. European attention remains focused on Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, and there is still some caution regarding full-fledged engagement with Syria’s new rulers.

As for China, despite its global revisionist ambitions particularly pronounced in Indo-Pacific, Beijing is expected to limit its involvement in Syria to economic cooperation.

Russia will seek to maintain its strategic assets, particularly the Hmeimim airbase and the Tartus naval facility. These are essential for Moscow’s broader military posture. While Sharaa maintains open channels with Moscow, he has insisted on measures to rebuild trust, including war reparations, reconstruction investments, Assad’s extradition, and the return of US$2 billion allegedly transferred to Russia. So far, he plays his balancing act pretty well.

Regional players: The new power brokers

The diminished role of global powers in Syria could create more space for regional players. The first foreign dignitary to visit Damascus was the Emir of Qatar. Sharaa’s first trips abroad were to Saudi Arabia and then Turkey. While these visits were significant and Riyadh and Dahua will have a say in Damascus, it is clearly Turkey that emerged as the biggest winner from Assad’s downfall. Its longstanding ties with HTS will now evolve into a “special relationship,” and there is discussion of a defense pact between Damascus and Ankara, potentially including Turkish military airbases in the central desert (Badiyah) or military training for Syrian forces.

This is closely monitored by Israel and even more the SDF, both of whom have reasons for concern. Turkey recently returned control of the Afrin region to Syrian forces and argues that the SDF should also hand over northeast Syria to Damascus. However, Ankara still holds other territories in Syria, including areas seized in Operation Euphrates Shield and a strip of land between Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain. It is unlikely to relinquish these territories soon, as they serve as a buffer zone against Syrian Kurdish forces.

Israel also stands to benefit from the new situation in Syria. For a long time, Israeli policymakers preferred Assad’s rule — the known devil — over uncertain alternatives. However, Iran and the Lebanese Hezbollah’s unchecked expansion in Syria became unacceptable. Regime change in Damascus is, in part, an indirect consequence of Israel’s military response to Hamas’s attack on November 7, 2023. That conflict subsequently weakened Hezbollah and Iran, creating an opportunity for HTS.

In Iraq, early pressure from Shia politicians and militias to support Assad militarily was reportedly deterred by U.S. and Israeli threats of airstrikes. With Assad gone, the Iraqi government has become more assertive in limiting Iranian influence. Baghdad now even signals a willingness to retain U.S. forces despite a previously agreed phased withdrawal.

The shift in Syria has also impacted Lebanon, facilitating the long-overdue appointments of a new president and government. The possibility of Syrian refugees returning home offers hope of easing Lebanon’s economic and social burden.

Need for sanctions’ removal

If the text highlights the increasing role of regional players in Syria, alongside the weakening influence of major powers, it should not be interpreted as a call for Western disengagement. This part is descriptive. On a prescriptive level, one has to emphasize the need for greater U.S. and EU attention to Syria as it once again becomes a geopolitical turning point with potential repercussions for the West and especially Europe. If it does not act, others will step in to fill the void. While a military footprint is unnecessary — except now in the northeast — Western support should not deprive the Syrian government of stabilization and reconstruction tools. These efforts could ultimately facilitate the return of more Syrian refugees, including those currently in Europe.

This means, first and foremost, easing international sanctions. The EU is about to finalize an initial suspension of certain restrictive measures, primarily in the economic sector. For its part, the Syrian interim government must reassure the West and regional donors that it does not pose a threat and is guiding the country in the right direction.

In a recent hearing on post-Assad Syria, Jim Risch, Chairman of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, outlined the main conditions for sanctions relief: 1. Partnership in counterterrorism; 2. The permanent exit of Russia and Iran; 3. Efforts to counter Assad’s methamphetamine trade; 4. Accounting for missing Americans; 5. A political transition.

The extent to which these or similar criteria will be enforced remains to be seen. A more lenient interpretation might already consider most of them fulfilled. Half a century of Assad’s rule over Syria plus more than a decade of brutal civil war cannot be erased overnight. Even thirty years after the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe, the legacy of the Iron Curtain is still visible — despite the West’s best efforts to assist from the very first days of transformation.

(Petr Tůma is a Senior non-resident Fellow with the Atlantic Council.)