Russia’s war against Ukraine is about much more than just capturing a few regions of Ukraine. Rather, all this is about Russia and China’s efforts to undermine the liberal democratic world order and construct a new one divided by spheres of influence, where Eastern Europe and Eurasia are under Russian domination while the Indo-Pacific comes under China’s sway. Picture source: Försvarsmakten, September 20, 2025, X, https://x.com/Forsvarsmakten/status/1969085627099394248/photo/1.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 54

The Harder They Fall: Strategies for Countering Russia and China

By Batu Kutelia

Blurred Red Lines of The World Order

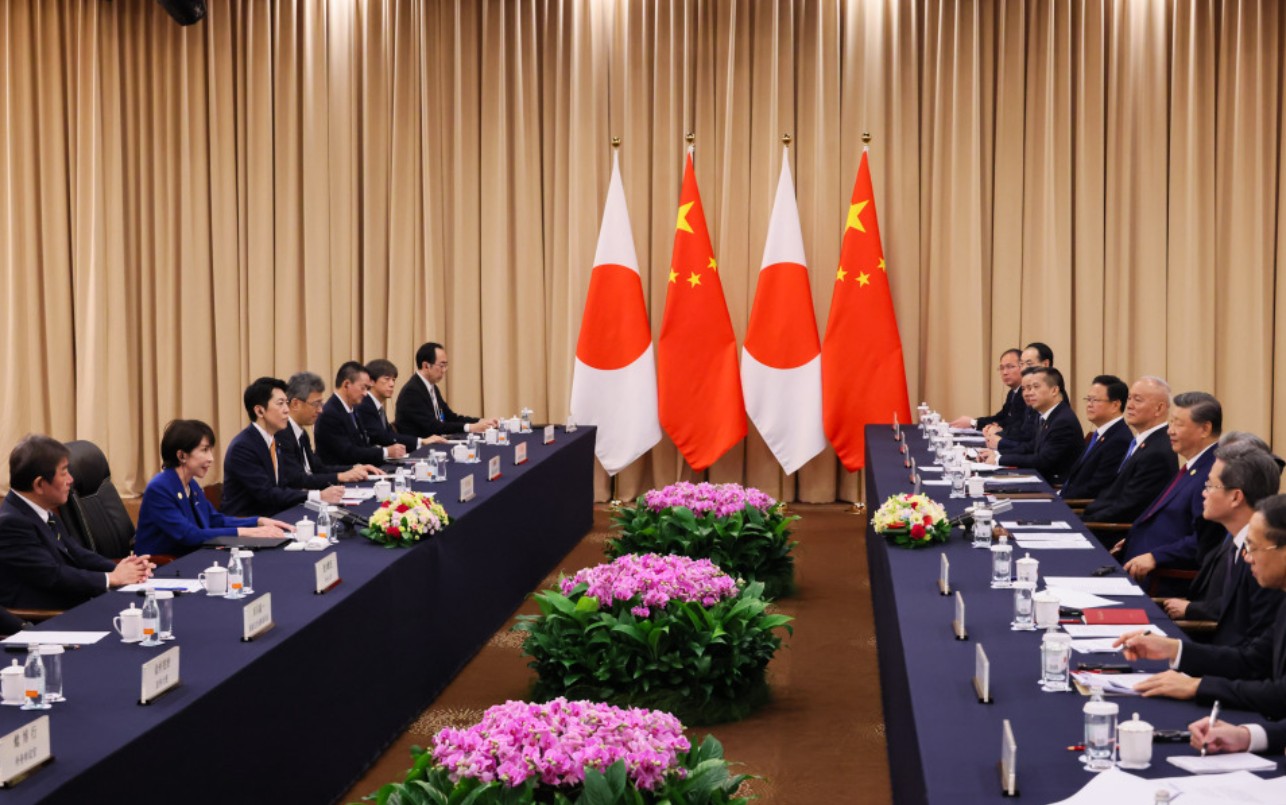

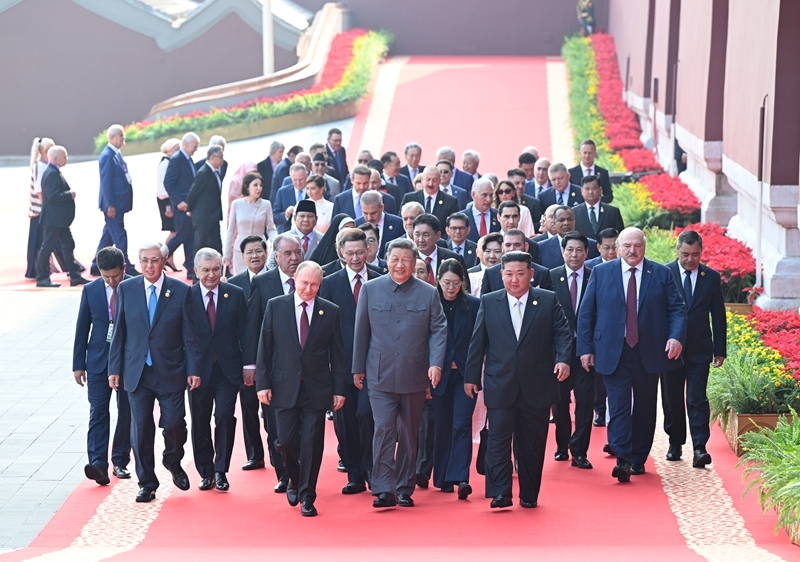

Russia’s war against Ukraine is about much more than just capturing a few regions of Ukraine, just as Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 was more than just occupying two regions of Georgian territory. Rather, all this is about Russia and China’s efforts to undermine the liberal democratic world order and construct a new one divided by spheres of influence, where Eastern Europe and Eurasia are under Russian domination while the Indo-Pacific comes under China’s sway. Although frictions could materialize between the two revisionist powers, currently they are tactical allies in this endeavor. Also, the key characteristics of power consolidation and projection have major similarities, including strongman rule, acting as “the man of his word” with a divine/holy mission of revitalization, and unification under civilizational identity.

Besides geostrategic redistribution, this vision of a new world order has no place for the rules-based international institutional arrangements, most particularly values-based collective defense and security alliances. That is why days before the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping jointly called upon NATO to overturn its enlargement decisions. This appeal sparked the opposite reaction — Sweden and Finland joined the Alliance. Russia’s primary sphere of influence focus, however, are former Soviet/communist bloc countries, where Putin aims to create a so-called “Russian World” in which Russia acts as the main security provider. Similarly, China is promoting the concept of Asia-for-Asians, with China as the primary security provider.

The contours of this new world order were announced as early as in 2007 by Putin at the Munich Security Conference. Since then he has, step-by-step, implemented this plan by filling the geopolitical vacuum created by the perceived withdrawal of the democratic West. In Georgia, in 2008, before the full-scale invasion, Russia started with airspace violations, at a time when the then-U.S. Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, was in Tbilisi. The same pattern was observed 17 years later, with Russian aircraft violating the airspaces of NATO countries Poland, Romania and Estonia, again testing the red lines. As always, weak responses triggered strong actions from the authoritarian regimes. Similarly counterproductive has been the policy of appeasement with which those provocations were responded to, including the “reset policy,” cancelling the European missile defense program, legitimizing land captures and the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan. All these were followed by full-blown aggressive moves.

Whatever the reasons for those strategic withdrawals, they made Russia more aggressive and the Sino-Russian alliance stronger and therefore more costly to counter. “The bigger they are, the harder they fall,” as the saying goes. There are major indications of the inevitability of this fall, but the consequences might be devastating if the situation is not addressed immediately.

Ukraine, while bravely resisting Russian aggression for three years, has yet to receive any definite security guarantees. Only some vague contours and several bilateral or multilateral defense and security cooperation platforms, including critical minerals, defense industry modernization and post-war economic rehabilitation and the blurred proposals of a peace agreement have materialized so far. For Moscow, any peace deal should equal Ukraine’s complete capitulation. If such an end state were imposed, the next move in the Russian hybrid offensive will be the capture of Ukraine through direct political interference and political manipulation through a network of corrupt enablers. A similar strategy was successfully tested in Georgia, where Russian oligarchs orchestrated a constitutional coup d’état through Russian interference. This state capture operation involved the exercise of hybrid offensive below the threshold of open military hostilities, influencing economic and political decision making of the targeted nation through fear of a renewed military offensive and lubricating it with corruption and propaganda.

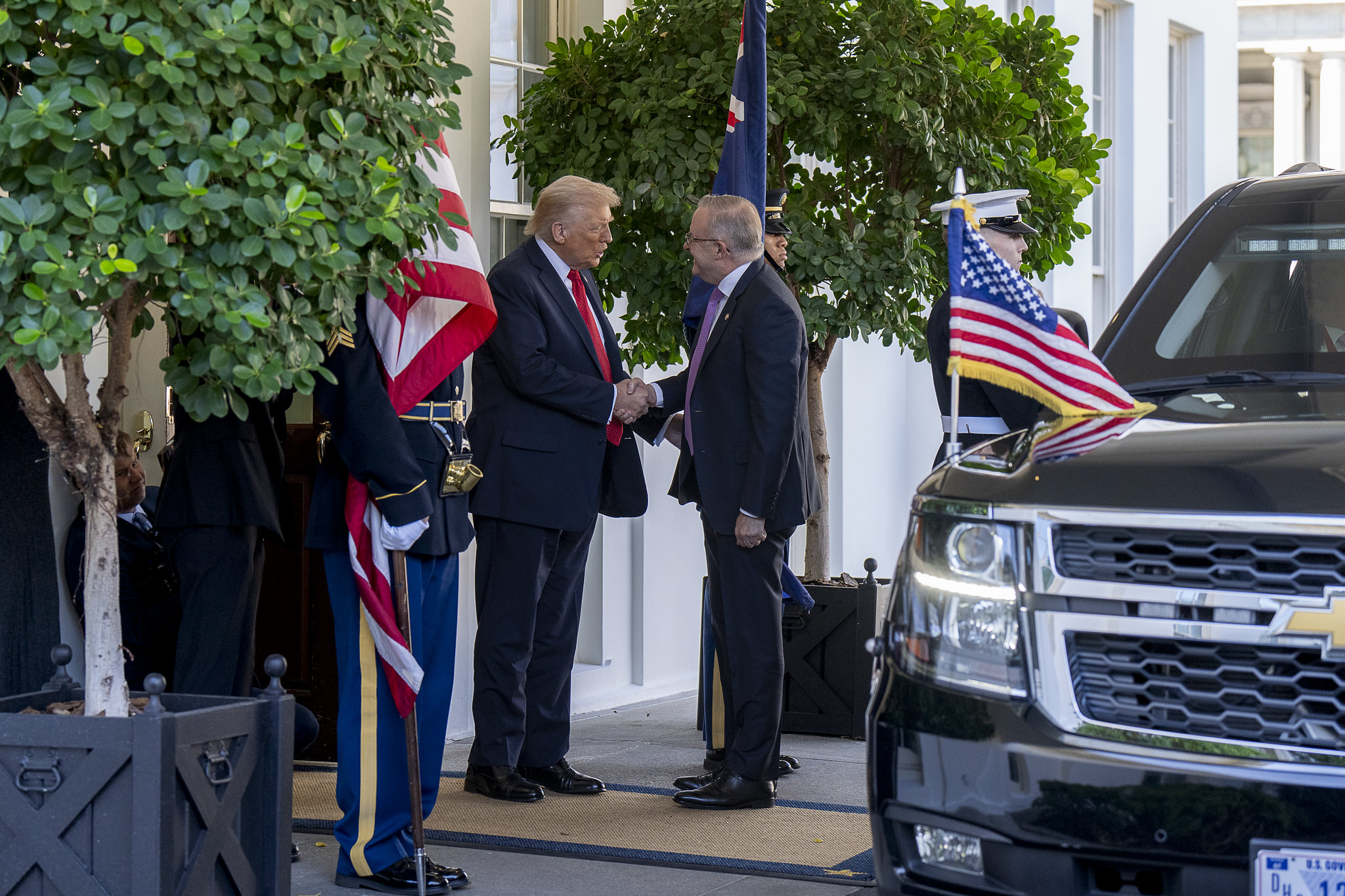

American Unilateralism and a Possible Double Win

Meanwhile, after more than a decade of U.S. withdrawal from key geostrategic regions, American interests have been challenged globally. American unilateralism may be the quickest response. Actions such as bombing Iranian nuclear facilities, regime change in Syria, a peace treaty between Azerbaijan and Armenia, direct diplomacy between India and Pakistan, and coercion of the Venezuelan regime, to name just a few recent endeavors by the U.S., could influence Beijing’s behavior. However, to a larger extent Chinese actions depend on how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine ends, and what role the U.S. and the Transatlantic Alliance will play in all this. Related to this are the reasons why Beijing has backed Russia’s war in Ukraine: to weaken Western unity economically, militarily and politically, and to gain an advantage over the war-weakened Russia and its economy.

The risk of dependency on U.S. unilateral actions as a deterrent is that it is the subject of domestic political cycles and challenges. The foreign policy priorities of the U.S. are vulnerable to constant change, particularly due to electoral cycles. As has occurred on several occasions in recent history, this might be seen as opening a window of opportunity for China to achieve its goals in the Indo-Pacific region — chief among them the annexation of Taiwan.

By solving the “Taiwan issue,” China would achieve its strategic goals of creating a “new reality” (a term often used by Putin). A successful military and political Anti Access/Area Denial infrastructure in the region aimed at the U.S. and its NATO partners. This could be compounded by effective hybrid operations below the threshold of open military conflict to achieve a dominating political influence (such as controlling supply chains and logistical routes), interference in other countries’ political affairs, and the ability to lubricate this process through corruption and propaganda.

Russian defeat in Ukraine, however, would endanger Beijing’s rationale for supporting Moscow’s invasion and therefore close its window of opportunity. This would change Beijing’s strategic rationale, or at least its tactics against Taiwan. Russian failure in Ukraine could also create an opportunity for normalizing U.S.-EU-China relations — a double win for the U.S. and its partners.

Lessons from Ukraine

For this to happen, democracies in the Indo-Pacific region and their Western partners should consider some of the lessons of the past, particularly those from Ukraine’s real-time lab of fighting war in the new era. In the context of modern hybrid warfare, when every aspect of social life can be weaponized, classical military deterrence is important but not sufficient. A combination of military, political, economic and societal resilience amplified by the will to fight in conjunction with strategic partnerships with a demonstrated highest possible interoperability (military, political and industrial) all contribute to strong deterrence.

In the case of effective military interoperability and regional alliances, China’s overwhelming military superiority will not be decisive if it is countered by coordinated, decentralized resilience, Western-standard mission command defense philosophy, air support and real-time intelligence sharing among partners. The ability to adapt existing weapons systems and technologies to the enemy’s changing tactics is the major factor. Autonomous platforms, AI-guided weapons systems and scaled up military industrial capacities will be key factors to secure this necessary agility.

The further integration of the economies of regional democracies on strategic components of scalable military industrial base, AI, quantum industries and innovation and modern nuclear energy technologies such as small modular reactors (SMR), would significantly elevate existing economic partnerships and the critical interdependence of democracies in regions of concern. In order to avoid a domino effect in the most critical fields, prompt and proactive measures against any chances of aggressive adventurism are absolutely necessary.

As to other aspects of the hybrid challenges facing democracies, particularly in the case of major crisis, the maintenance of a national resolve and will to fight, unity, and a whole-of-democracies approach to resilience will ensure continuity of government and critical government services, resilient food, water, energy supplies and functioning transportation systems, civil communications, financial, economic and medical systems, the ability to deal with mass casualties and uncontrolled movement of people to de-conflict these movements from military deployments, and resilience to information influence operations.

The only chance for long-lasting peace in Europe and in the Indo-Pacific is through deterrence and by exploiting the internal vulnerabilities of Russian and Chinese political and economic systems. In short, rephrasing Margaret Thatcher’s toast to Reagan, it’s time to put freedom and democracy on the offensive.

(Batu Kutelia is a Senior Fellow at Delphi Global.)