This long overdue meeting has on the whole allowed a lowering of the temperature between the two superpowers. Nonetheless, most of the contentious issues between Washington and Beijing have remained unresolved, and the root causes of the U.S.-China rivalry are unlikely to fade away.

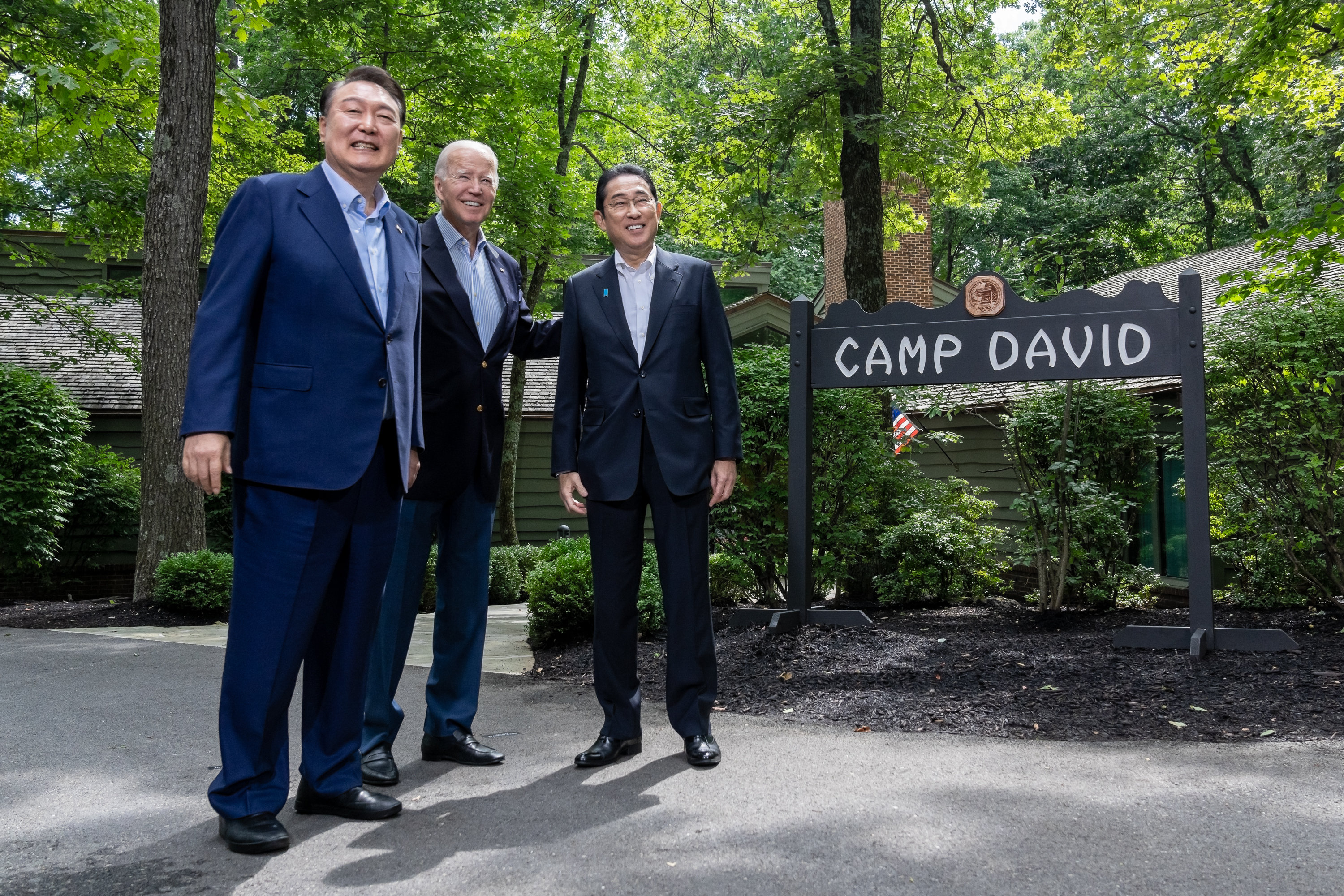

Picture source: President Joe Biden, November 16, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=915715697222061&set=a.35664939979536.

Prospects & Perspectives No. 62

The Biden-Xi Meeting and U.S.-China Relations

By Jean-Pierre Cabestan

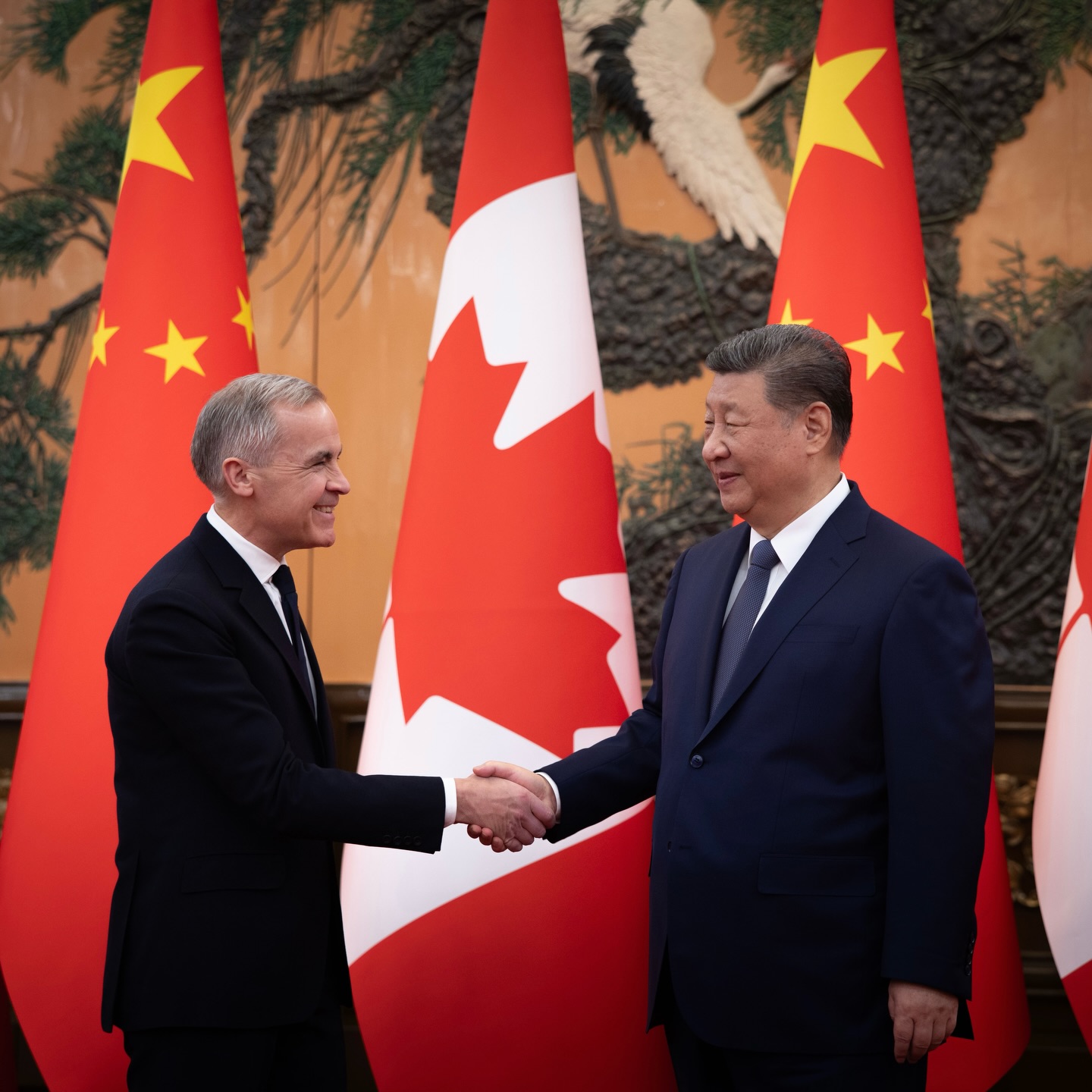

United States President Joe Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping met on November 15, 2023, in Woodside, near San Francisco, on the sidelines of the APEC Summit. It was the first time since their previous face-to-face meeting at the G20 meeting in Bali, Indonesia, a year ago, that the American and Chinese heads of state met. This long overdue meeting has on the whole allowed a lowering of the temperature between the two superpowers. Nonetheless, most of the contentious issues between Washington and Beijing have remained unresolved, and the root causes of the U.S.-China rivalry are unlikely to fade away.

Many commentators have praised the quality of the four-hour meeting between Biden and Xi in the historical estate of Filoli. Presented later by Biden as one of the “most constrictive and productive discussions” he has had with his Chinese counterpart, the meeting has indeed facilitated the conclusions of two important agreements: Beijing’s acceptance to reopen high-level communication channels between U.S. and Chinese militaries, and the creation of a counter-narcotic working group aimed at cracking down on Chinese exports of the ingredients for fentanyl.

In the aftermath of the Biden-Xi meeting, the Chinese president delivered a well-received speech in front of the American business community, trying hard to attract more foreign investment and technology in the context of an unprecedented economic downturn at home and despite an overall difficult relationship with the U.S.

The Resumption of Mil-Mil Relations and Potential Crisis Management

Suspended by Beijing after then-House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022, U.S.-China military-to-military communications can help both governments manage incidents between their respective navies and air forces. According to the White House readout, both sides have decided to also resume U.S.-China Defense Policy Coordination Talks, U.S.-China Military Maritime Consultative Agreement meetings and telephone conversations between theater commanders. This is arguably the most fruitful outcome of the Biden-Xi meeting.

In the last few years, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy and Air Force have taken increasing risks to try to convince U.S. or U.S. allies’ naval ships and military airplanes not to enter the vast maritime domain the People’s Republic of China (PRC) claims in the South and East China seas or around Taiwan. As a result, the risks of collision have dramatically increased since neither side is ready to back down: the U.S. military will continue to sail and fly wherever international law authorizes it to do so, including in the PRC’s claimed Economic Exclusive Zone; and the PRC will persevere in its attempt to dissuade other navies and air forces from penetrating within the nine-dash line in the South China Sea, the Taiwan Strait or the Air Defense Identification Zone that it created in the East China Sea in 2013.

The question is whether the restoration of U.S.-China mil-mil relations will help. After meeting with Xi, President Biden told journalists that both presidents had “agreed that either one of us could pick up the phone, call directly, and we’d be heard immediately.” But Beijing authorities’ track record on this practice is far from convincing. In the past, when a problem or a crisis broke out between both militaries, the hotline usually revealed itself to be non-functioning. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the U.S. and China will not be able to communicate in such cases in future. The EP-3 incident in 2001 demonstrated that diplomats, rather than the militaries, on both sides are arguably the most appropriate negotiators in case of crisis. But rapid communication, especially among theater commanders, when problems occur remains to be tested.

Yet, the reactivation of contacts between the U.S. Secretary of Defense and the Chinese Defense Minister, once Li Shangfu’s successor is appointed, as well as other mil-mil meetings, will allow both military establishments to better understand the other side’s red lines and hopefully decrease the risks of a military crisis.

On fentanyl, Biden was clearly facing a domestic audience; this synthetic opioid is responsible for 70,000 overdose deaths in 2022 in the U.S.. The Chinese government can put pressure on Chinese companies producing fentanyl’s ingredients, but it is likely that the Mexican cartels which manufacture the drug will work quickly on finding new suppliers in other countries.

Manage US-China Competition

In many respects, after San Francisco the U.S.-China relationship remains where it was after the Bali meeting. Biden’s key objective is to set a “floor” to prevent the relationship from “veer[ing] into a conflict” — in other words, war. Nonetheless, this time, it appears that the PRC has accepted the idea that both powers are competing, and that this competition needs to be managed and is manageable, if managed “responsibly.”

It should also be noted that Biden and Xi agreed to cooperate on artificial intelligence and climate change. Moreover, they have promoted the expansion of people-to-people relations between both societies, relations that have been strongly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic.

On Taiwan, China’s pressure remains strong and arguably is getting stronger, and Xi asked that the U.S. support “peaceful unification” and stop providing defense equipment to Taiwan — stances that no American administration is likely to endorse. Xi also reminded his interlocutor that Taiwan’s “reunification” is “unstoppable,” although one can suspect that in making this point the Chinese leader was talking more to his domestic audience than to Americans. True, Biden has repeated the usual mantra on his country’s adherence to the “one China” policy and has avoided mentioning his pledge to defend Taiwan if the latter were attacked. However, Biden asked the PRC to “restrain” its military activities around Taiwan and not to interfere in its presidential and legislative elections next January.

A More Stable Relationship?

Are we heading toward a more stable relationship between the U.S. and the PRC? It is clear that competition currently trumps other features of the relationship. Moreover, this competition is not only geo-strategic but also of technological and ideological nature. In other words, it includes the major ingredients of the old Cold War. Moreover, today “de-risking” is an open policy in the U.S. and a discreet one in the PRC. Nonetheless, both the U.S. and China are aware that full economic decoupling is not only unlikely but impossible in view of the multiple vested interests — e.g., many large multinational companies active on the other country’ soil — that contribute to binding both sides to each other.

Moreover, the economic downturn in the PRC has probably convinced its leaders to adopt a less confrontational tone toward the U.S. as well as U.S. allies in general. In the coming years, Xi will need to concentrate on domestic issues, such as the crisis in the housing sector, youth unemployment, an aging population, the growing cost of healthcare and, more generally, a social malaise that Chinese Communist Party (CCP) propaganda has had a hard time mitigating. Still widely used a year ago, the “The east is rising, the west is falling” (Dongsheng Xijiang) slogan seems to have moved to the back-burner in Beijing. This is reassuring for Taiwan and global stability. Yet, the PRC’s ambitions are far from having disappeared. When Xi stated “the world is big enough to accommodate both countries,” this was only partly reassuring: indeed, risks of war may have diminished, but it is no more the Asia-Pacific region but the whole world that is now the theatre of U.S.-China competition, a competition that, we must emphasize again, is not only geo-strategic but also technological and ideological. In other words, while more multipolar than in the past, the world is clearly structured around this new U.S.-China bipolarity and rivalry.

(Dr. Jean-Pierre Cabestan is Senior Research Fellow, Asia Centre, Paris.)